Despite the torrent of work, the early symptoms of motor neurone disease were apparent. Simon knew in his last years that he was working against the clock: in his final months his right hand was still rock steady, but had no longer the strength even to hold a pencil. His last commission, two years ago, was a goblet made as a retirement gift for the head of his old school, Stowe.

Then he wrote a strange and fascinating book, On A Glass Lightly (2004), part memoir, part catalogue of a lifetime in glass. He described it as a rite of passage, a one-sided continuation of a lifelong conversation with his father. “It seems strange that it has been done in his absence, so he couldn’t answer back,” he told me in December 2004. “I had him looking over my shoulder all my life as an engraver – and for me, in writing, the book also had him as a shadow.”

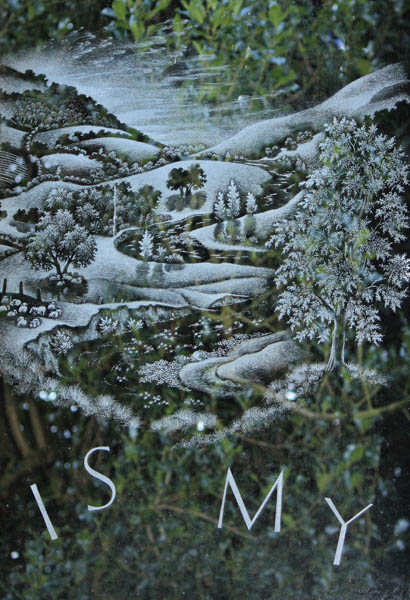

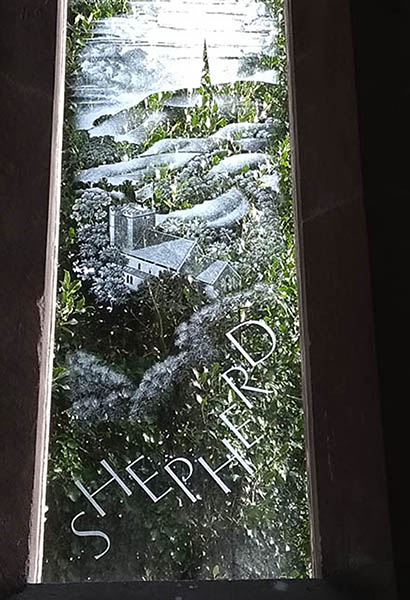

Although they were so close, frequently working side by side, exhibiting together, and consulting one another on work all their lives, his relationship with his father was never easy. His mother, the beautiful actor Jill Furse, granddaughter of the poet Sir Henry Newbolt, died after giving birth to a daughter, when Simon was only four. Although cherished by his grandparents, he felt his father was unable to demonstrate the affection the small boy craved. One of his most beautiful pieces was an engraving of his grandparents’ Devon home, an evocation of childhood happiness.

Their working relationship was equally uneasy. He was 10 when he engraved a violin on a tooth mug. His father spotted and fostered the talent but, Simon felt, also tested and judged him harshly. As a student, home from Stowe or the Royal Academy of Music in the late 1950s, he was often set tasks which would have absorbed the entire holiday. In the long hot summer of 1961, when Simon just wanted to play croquet, he failed to finish executing Laurence’s designs on four decanters, resulting in the late delivery of a commission: the father was enraged, the son anguished. He still felt the guilt more than 40 years later, and included illustrations of the two surviving decanters in his book. His music took him around the world, playing the viola with ensembles including the English Chamber Orchestra, the Orchestra of St John’s Smith Square and the Orchestra of the Age of Englightenment. His great love was chamber music: he performed with the Georgian quartet, Hausmusik, and appeared as a guest with the Salomon quartet. His music career lasted for 30 years, until he felt he had to choose – and chose glass.

In 1971 he married Jennifer Helsham, an Australian musician. They divorced in 1994. In 1997 he married Maggie Faultless, of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, who survives him. Simon died fearing that the art he and his father recreated and perfected might die with them. There is no full-time course in glass engraving in the country, a fact he described, sadly, as “reprehensible”.

Simon Whistler, engraver and musician, born September 10 1940; died April 18 2005.